My school sat atop a hill, overlooking the ocean along the Caribbean coast of Colombia, on the outskirts of a city named Barranquilla. In those classrooms I would sit by the window, my eyes tracing the contours of the sea, pondering how the same water my gaze touched had surely touched the shores of Florida and the Gulf of Mexico. How arresting, yet how fundamentally uncomplicated it was, to see water that may have brushed against distant lands I hadn't visited—lands I had only heard about through my grandparents and friends who had been there. Foreign lands I had imagined many times while sitting in that classroom during geography class, sketching them on maps, tracing their contours onto white “bond paper.” Maps I first sketched in pencil, then retraced in ink using a black "stylish pen." River lines in blue, city dots in red

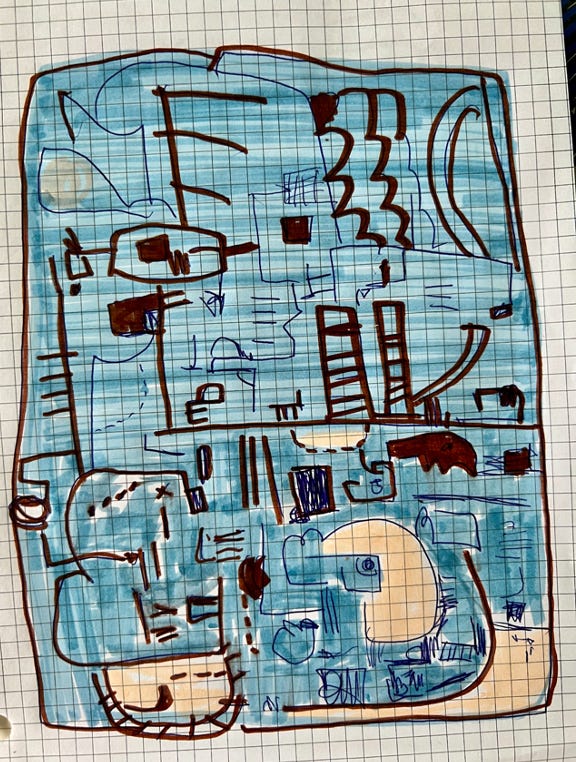

Through this process of map drawing, I developed a unique connection with borders, land, and water. Drawing maps gave me insight, an intuitive understanding of how these geographical features were manually created through lines, grids, and geometry—elements that later emerged formally in my paintings.

The lines I drew on my maps felt intentional, artificial, inconsequential, man-made, yet they had to be accurate, true to the source—the atlas. While tracing, no matter how precise I was, a feeling of uncertainty would fill me. What if the border line I traced wasn't exactly where the atlas line was? What if a country grew or shrank by millimeters due to my hand trembling? My lack of precision? A distraction? And what if my ink smudged? Would the border alter? Shift? Vanish in my hands?

I visited the United States for the first time when I was 14 years old. I had never been to a foreign country. I had never flown. My first impression from the plane window landing in Miami was how organized the urban landscape was. Neighborhoods perfectly demarcated by manicured lawns, streets parallel and perpendicular to each other forming oceans of concrete grids, pools every two houses that registered like little blue squares from above, the water movement flattened by the distance. This precision mesmerized me.

This fresh paradigm of spatial arrangement stood in stark contrast to the view I had just seen two hours earlier departing from Barranquilla, an aerial landscape that danced to its own rhythm, careless and spontaneous, as if no one was watching. I wondered if Americans down below could see the patterns built especially for them to circulate, to move, to flow.

Upon my initial step upon American soil, I continued to confront this unyielding rigidity, this geometry of control. I saw it on the I-94 immigration form laid out with boxes reserved meticulously for each letter of last names that never truly fit. I saw it on the immigration officer’s demeanor when he asked for my i-94, in the cubicles that conformed to a square shape where the immigration officer sat, in the perfectly formed straight lines to get to the cubicles, in the laws that enforced such lines and cubicles and i-94 forms. It was in this rigidity that I saw how everything just flowed: bicycles, buses, people in cars–so many cars–in perfect order, on perfectly straight roads, green light, red arrow, 4-way stop, 2-way stop, merge, yield, go, exit.

It was fairly recent through drawing that the recollections of those maps, etched during my school years, resurfaced. The lines materialized before my eyes, the conventions assumed significance, and the fear of ink altering the borders became a fantastical image. Only through the act of drawing I have managed to externalize my observations, the tension I described between the exactitude of the landscape and the impulsivity of human movement, between the rigid and the free flowing, perhaps even between the Caribbean and the expanses of North America.