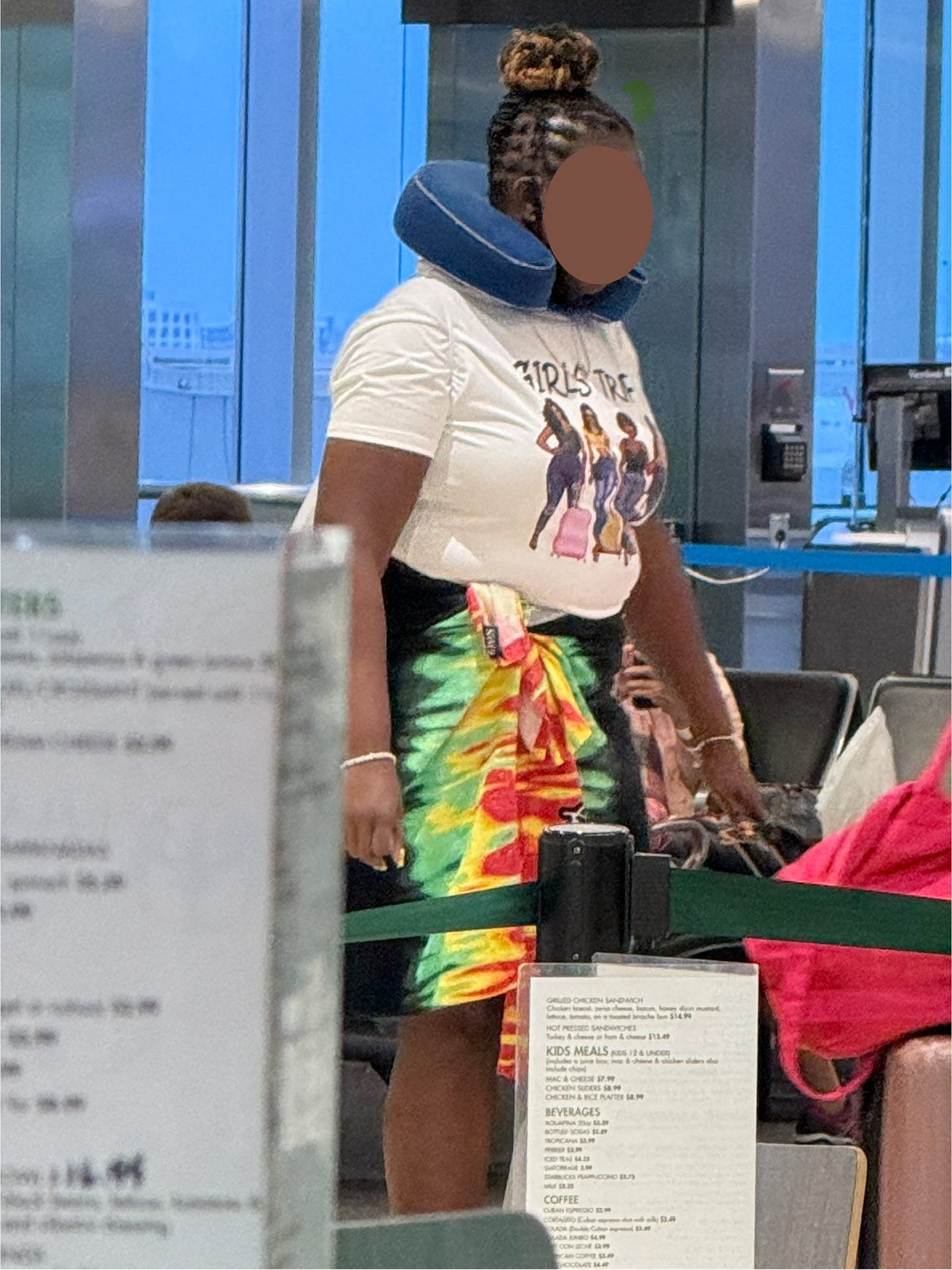

Last week at the Miami Airport, I saw a lady wearing a towel as a skirt. As she gleefully boarded a plane to Montego Bay, I wondered if towels were standard attire in Jamaica. I wondered if I would have considered her outfit fashionable had The Row not already told me it was.

I was at the airport last week as I went on an impromptu 5-night trip to my hometown. My mom was going to celebrate my niece’s 18th birthday so I decided to bring the girls to Colombia for the big celebration.

I knew today’s post was naturally going to be about the trip, specifically about the fact that I intuitively packed only pants to go to an all-year hot town in the Caribbean where, as I’ve mentioned way too many times, most women wear flowy dresses and cork platforms. Where you’d look like you were trying to make a statement by wearing anything different from this:

Still in Terminal D, I saw another young lady traveler wearing that Toteme wool cashmere coat. The fleeting 3 seconds of her walking towards me and the way the coat moved prompted me to look it up as soon as she disappeared from my sight. It was the soft taupe against the taupe from her sweats and white sneakers and black long straight hair.

Did I want her coat or did I want the way the coat fit on her petite frame? Did I want her outfit or her cool modelesque long textured black hair moving in unison with the wide lapels? The fact that she looked like she was an editor at Vogue going on a shoot in Courchevel?

I sat to eat breakfast with my daughters at Versailles, the airport location of the quintessential Cuban restaurant where the waitress who kindly tailored Bianca’s order to her multiple allergies looked like a Margiela-era-Hermes. Except she was wearing a Guayabera shirt. Like the ones I made our guests wear to my daytime summer NYC wedding to give the event a “Caribbean touch.”

Right before boarding, there it was. The Alo set all the young girls wear at my local pilates studio. Except this time paired with a Colombian mochila

I immediately thought of my previous post, of Shadia Farah’s words:

Misconceptions persist—people often see Caribbean culture as lazy or folkloric, making it difficult to be taken seriously in certain spaces. For that reason, I tend to avoid stereotypical Caribbean aesthetics like floral prints and bright colors and I don’t intentionally assert my Caribbean identity—sometimes, I even feel like I run from it. I don’t even wear mochilas outside of Colombia, and if my style reflects my Costeña roots, it’s been an intuitive process rather than a conscious choice.

I got curious about her statement of not wearing mochilas outside of Colombia. Of not deliberately asserting her Caribbean identity. She made me question forced performances of nationality and identity. Like the guayaberas at my wedding. I thought about how our bodies become a space to perform patriotism. I wondered what the limits were between harmless patriotism and dangerous nationalism.

I immediately sent Shadia 5 lengthy and honestly embarrassing voice notes saying that, just like her, I love Colombian mochilas but refuse to be exoticized. That I love many aspects of my culture and its symbols, but don’t love anything that feels like an imposition. That I refuse to be shamed for not wearing the “right” Colombian thing. For not using the “Colombians do it better” hashtag. That, personally, I refuse to perform stereotypes of the hypersexualized Latina. That I don’t judge women who perform those scripts—in fact, I admire many of them (Sofia! Kali-Uchis! Salma!) but I don’t want to be judged for not doing so. That I emphatically refuse to follow monolithic ideas of womanhood.

I breathed.

Still at the gate, I thought again about the contents of my carry-on. I thought about the easy t-shirts. Took a mental inventory of the accessories. And the flip-flops, which I disliked until Leandra Medine Cohen not only made a case for them, but rendered visible the class bias that had made flip-flops undesirable for me in the first place: in Barranquilla, they were worn by maids. I realized I had absorbed the tacit—and sometimes explicit—warning that looking like a maid in my hometown’s social circle was a mortal sin. That smelling like the cheap face powder they got in corner tiendas, even if that was all I could afford, was sacrilegious. That painting my nails hot pink, like they did to hold our bodyweight on the monkey bars and wash our dishes, was grounds for excommunication.

No. nice girls wore proper sandals, powdered their faces with Clinique, and painted their nails with french tips or Chanel’s ballerina.

We made it to Barranquilla without inconvenience. I felt good about everything I brought and wore. I packed it all in less than 10 minutes without hesitation. I didn’t buy anything for the trip. And it all felt like (the idea I have constructed of) me.

The inspiration was clear:

My mom. Or the memory I have of her while I was a girl.

I’ve written before about how she shaped my style, how she shaped my understanding of femininity. About how she taught me that there is no fixed way to be a woman. Or a mother. Or Caribbean. Or anything, really.

She was feminine in pants and loafers as a working woman in the 90’s. She was beautiful without cork platforms. She was elegant with unmade nails. She was a great mom even if she worked a lot.

I’ve written about how my dad and her worked really hard, and together they made just enough money to save us from precariousness, a state we constantly hovered on the edge of. My mom, however, was successful in a man’s job, wearing mostly men’s clothes, being the main breadwinner of our household, all while staying in her feminine energy. When I tell her I wish I had done a quarter of what she had accomplished by the time she was 35, she reminds me to appreciate the opportunity to stay home with my kids. To see value in the time I spend with them. To understand that I don’t need to be her.

I try.

During our trip, while eating breakfast in our hotel dining room, surrounded by foreign women recovering from fresh facelifts and mommy makeovers, some with the bright eyes of someone reclaiming her body, others with the vacant gaze of exploitation—I finally asked my mom why she chose pants, loafers, and men’s shirts over skirts to go to work every day.

I always assumed it was because she deliberately rejected traditionally feminine codes in order to be taken seriously in men’s spaces. I was wrong. She didn’t care about what men think. She did it purely for comfort—simply because she wanted to sit at her desk and not worry about accidentally flashing her underwear.

She did this for almost 3 decades. Until Barranquilla stopped being a place where she could continue living by her principles. That was when she left, to start over in her 50s, doing jobs she was overqualified for, but in a country that opened the doors for her and allowed her a dignified and safe life. For her and for all of us.

One day in 2007, shortly after finishing law school, I came to visit her. I was heartbroken, lonely in Colombia, unsure about my future as a lawyer, and I missed her. I told her I didn’t want to go back. She not only understood—she encouraged me to stay in the U.S., to embrace my dream to study art, and to start a new life here. That trip changed the course of my life.

Last week felt just as earth-shaterring.

My mom was traveling to Barranquilla to join on my niece’s birthday celebration, and I knew my daughter was going to miss her, as she always does when my mom travels. She likes to be near her. Follows her from room to room. Sleeps in her bed when she feels like it. My mom lives next door. She always leaves the door unlocked.

So when the opportunity came up—on a whim, as an impulse, impromptu, just like my trip in 2007—we said: let’s all go back to Barranquilla.

So we went back home. Back to the beginning. Together for the first time.

<3, Laura

I just love your writing. Thank you for sharing your thoughtful reflections. Seeing your post in my feed makes my day ❤️

So beautiful 😍