The Row’s unexpected connection to Colombia’s Indigenous style

personal reflection on originality, perception, femininity, luxury, and exclusivity.

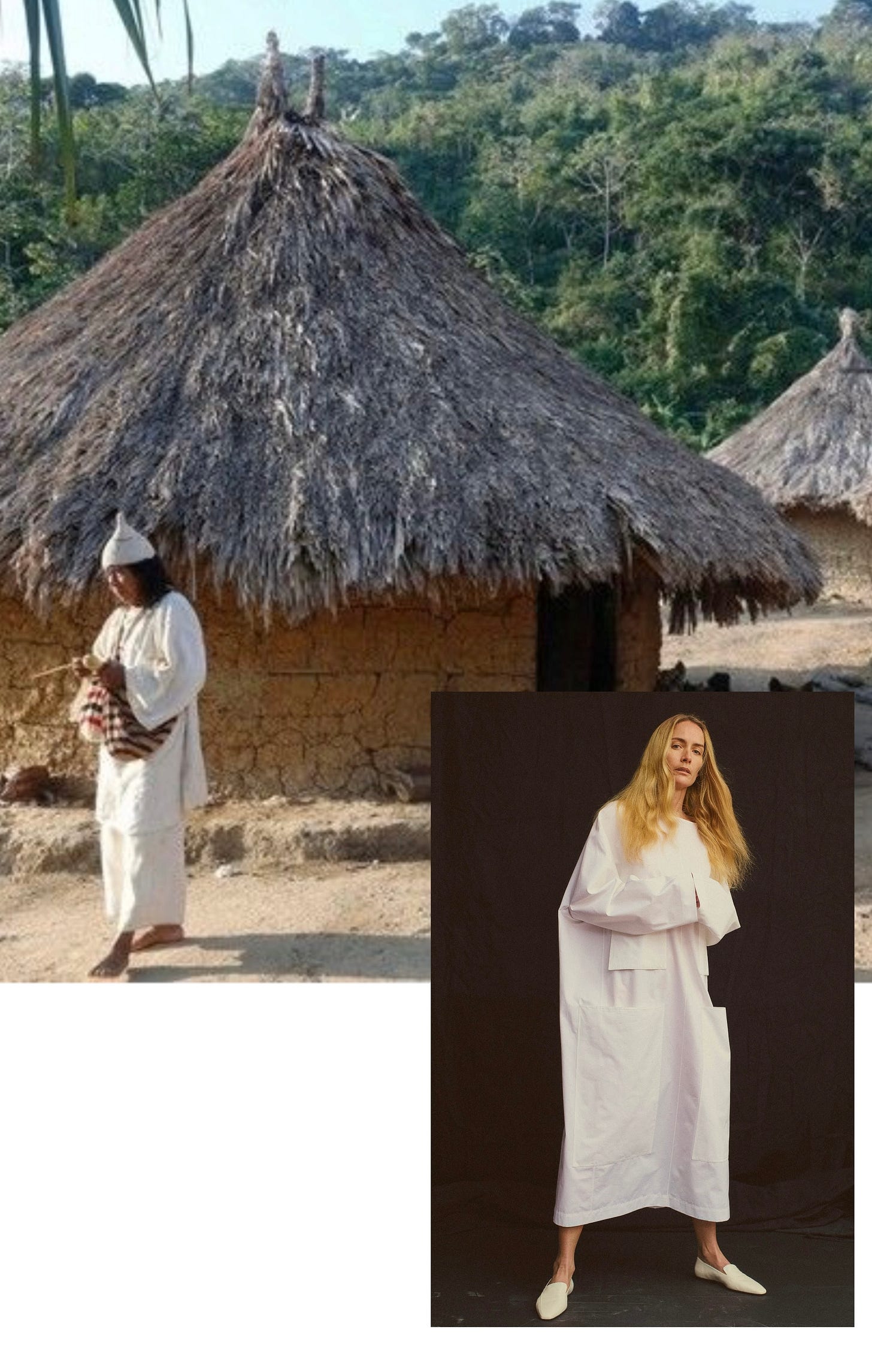

In 2014, when I first started paying attention to The Row, I couldn’t articulate why its aesthetic felt uncannily familiar. Soon enough, it became diaphanous—the shapes, the proportions, the way the garments wrapped the body, the structured midi tunics over voluminous pants, the waist-cinching fabric belts, the hats, the sandals…

it all reminded me of something I had seen before, when I was little, on family trips to Santa Marta where I first saw the Arhuacos and Koguis, Indigenous descendants of the Taironas, living in the most magical mountain range along Colombia’s Caribbean coast: the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta.

They have survived colonization, decades of government neglect, and the brutal violence of marxist guerrillas, drug cartels, and paramilitary groups.

For years, I have been looking at them. Something about their way of life, how they carry themselves, their resilience, and especially their fashion choices have always fascinated me. Since I was a little girl.

One day, the mental image became legible as I added a picture from The Row to a Pinterest board called “Style.”

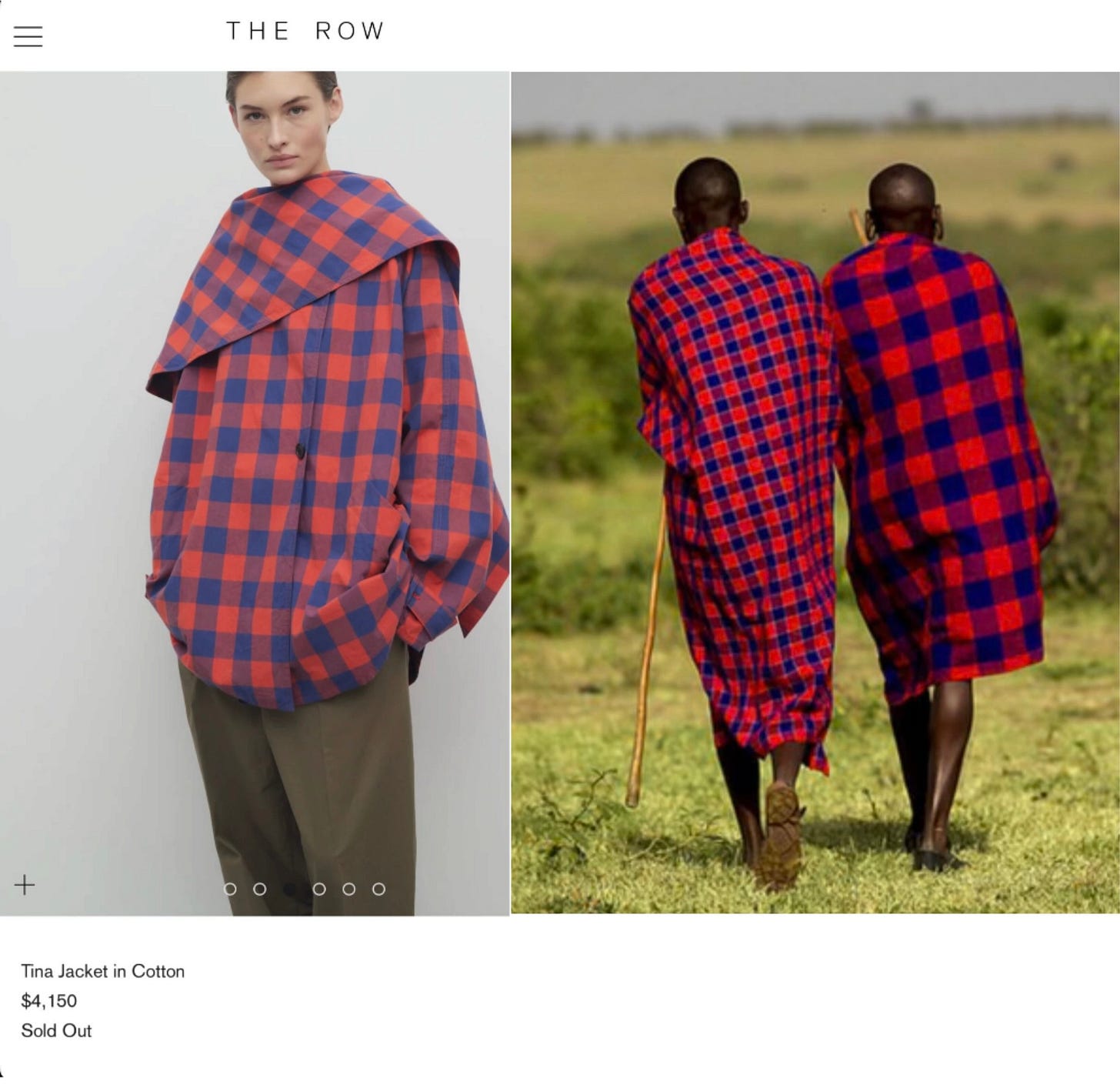

Now, I am not stating beyond a reasonable doubt that Mary-Kate and Ashley Olsen copied anyone. Diet Prada is so 2013, and at the end the of the day, we are all speculating. Cathy Horyn might trace The Row’s aesthetic back to Yamamoto’s sculptural restraint. My friend Gigi might see echoes of Moroccan or Middle Eastern dress. Some may feel Varvara Stepanova vibes. Some may see ultramodern clothes without a connection to the past. I see Koguis and Arhuacos. Ultimately, we’re all just connecting dots. Indulging in the pastiche:

Back in 2014, the dots I connected went beyond silhouette: the techniques—handwoven textiles, natural fibers, an emphasis on craftsmanship over trend—align with Indigenous garment-making practices and aesthetics.

The color palette, too, leaned into tones similar to the Arhuaco and Kogui clothes, shades that felt organic rather than industrial, literally dyed by direct contact with nature.

The true quiet luxury.

〰️

In 2014 I was also expecting my first child, and then more than ever, I wanted to dress like an Arhuaca. Why not? La Sierra held great significance for me. It was the first place where I experienced cold weather, where I ran freely with my siblings, rolling down hills—the same hills and mountains we could see from our window in Barranquilla. On clear days, 120 km away, there they were, the snowy peaks if we got lucky, a miracle on the horizon.

But no matter how much La Sierra meant to me, how deeply I loved mochilas, or even the high percentage of Indigenous ancestry revealed by my DNA test, I wasn’t Arhuaca. I hadn’t walked their path. My upbringing and experiences were entirely different, despite our physical closeness and shared nationality. Their clothes weren’t just garments; they were sacred, imbued with symbolism I couldn’t begin to understand. They weren’t even for sale. Unlike The Row’s, their clothes were not a product for consumption.

Yet, Arhuaco clothing evoked something I deeply yearned for—an aura of protection, tranquility, and elegance. Perhaps I could have found it within myself, but at the time, I was too overwhelmed for that kind of inner work. Living in New York, working in healthcare advertising, and dealing with the daily ache of pelvic ligament stretch pain, the only way I could access that feeling—stripped of its true significance—was through The Row. Except, I couldn’t afford it.

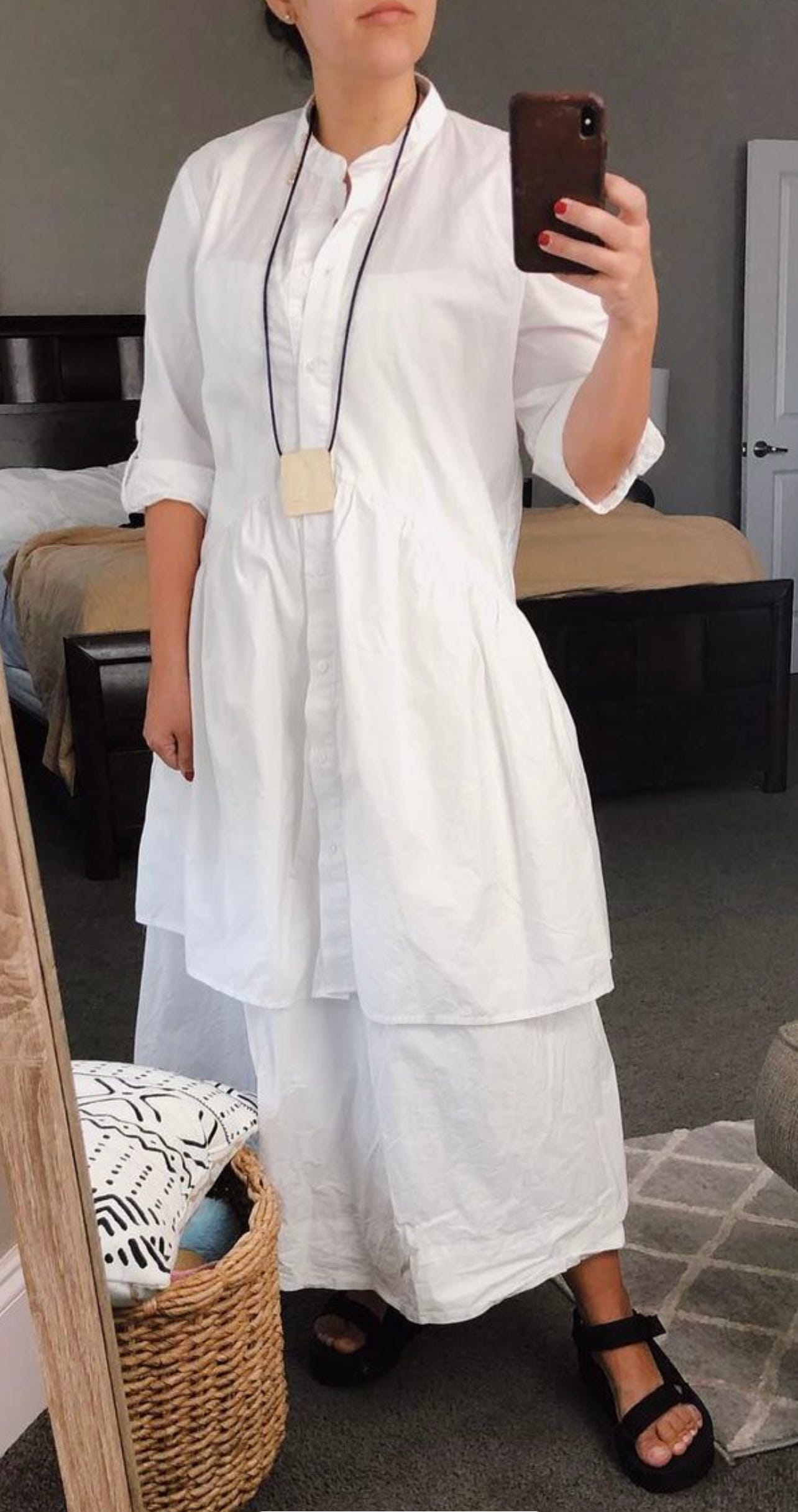

I didn’t give up, I kept searching for that feeling—externally, that is—until I found other brands that offered something similar— Elizabeth Suzann, Lauren Manoogian, and, of course, Eileen Fisher, whose store at Columbus Circle was the closest I could spiritually feel to La Sierra’s Ciudad Perdida.

Later I understood that what drew me most to this aesthetic is its interpretation of femininity. Because in the Caribbean-Colombian mainstream women fashion, beauty was often equated with exposure—cutouts, body-conscious fits, sans-back-pocket tight jeans. And Arhuacos, Koguis as well as The Row subvert this stereotypical idea of femininity entirely. Whether deliberately or not, the beauty is not in revealing, but in sculpting. And that attracted me. They offered something new, in between the feminine, easy breezy summer dresses of the Caribbean and the understated minimalism that I admire from my mom.

The clothes molding the body rather than displaying it, creating shape through structure and drape rather than skin. It is no coincidence that around the same time, I fell in love with other designers that do it well too: Phoebe Philo for instance.

This was a revelation for me. As well as to many women who were looking for that feeling.

In 2015, when my post-pregnancy body wasn’t something I wanted to showcase, and to this day, this approach to dressing gave me the ability to shape it on my own terms. It made me feel pretty.

〰️

Clothing has always been a symbol of status, hierarchy, and identity. From ancient civilizations to modern fashion, garments distinguish social classes, confer authority, communicate belonging. The Koguis and Arhuacos of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta are no exception. Their clothing is full of meaning. The Mamo’s hat is not merely an accessory—it is reserved for men and signifies wisdom and spiritual leadership within the community. Just like the Row’s hats symbolize acquisitive power (or credit card debt,) cachet, certain style know-how.

This is a universal impulse. Even in societies that reject material excess, even before capitalism, distinctions signaling through clothes remain. Whether in the gold ornaments of the Taironas, the elaborate tilmantli of the Aztecs, the hats of the Affranchis, or the cashmere coats of The Row, clothing has always carried meaning beyond function.

However, elegance exists in the cotton tunics of the Arhuacos and in the raw silk tunics of The Row. They both cover, protect, suggest a way of moving through the world.

And yet, only one is called “luxury.”

But why?

Why does an Indigenous garment, handwoven over months, remain an artifact, while a dress from The Row, cut in a Manhattan studio, becomes fashion?

Why do the same design principles—simplicity, craftsmanship, timelessness, economy of elements—signify refinement in one context and mere folklore in another?

Who establishes these borders?

〰️

Growing up, I saw social class not as a barrier to happiness but as a structure that shaped access to certain spaces—a fact of life. We had far less money than those in our circle, but my grandmother’s last name, as well as my parents’ grit and work ethic, opened a few doors. I attended a private school in Barranquilla, and I understood the codes. In general, I was treated with kindness, yet I was never inside my town’s top circles. Not that I resented it or aspired to be. I knew my place, and as long as my basic needs were met, I had meaningful relationships, and I had a sense of belonging, class distinctions or not being part of the country club didn’t really keep me up at night.

Maybe that’s why I don’t see fashion’s inherent exclusivity as something that needs to be dismantled. Its mere existence doesn’t bother me, nor does the fact that I can’t access all it offers—except maybe when its inner workings prevent those who deserve to rise to the cusp from being seen. When it dictates whose work is visible, whose talent is recognized, whose merit leads to social mobility, who gets opportunities, and who is left on the margins.

Maybe that’s where I draw the line. Or where side-by-side comparisons become not only necessary but unavoidable.

️

Laura, I enjoyed this piece so much! The Row’s connection to indigenous Colombian attire is indeed unexpected and uncanny. I would agree with you that’s it’s impossible to say if it is where the row definitively got their influence as there are many indigenous cultures who employ similar forms and techniques. Who knows if indigenous design is specifically the influence. But for the purpose of your connection to their design, what’s interesting to me is the meaning you ascribe to it based on your own history and culture. It reminds me of my silk/linen TooGood spinner dress - I’m 💯 sure that they didn’t model the dress after the hanbok, but over time, the shape has made its way into modern vocabulary and when I wear it, I feel like I’m wearing a hanbok and a connection to my history.

Laura your writing truly blows my mind. I am struck by the question of what is fashion vs. what is artifact. I'm struck by the spectrum of femininity through exposure vs. shape through structure. The through line you drew from Arhauco to you and The Row. So, so well done. As always.