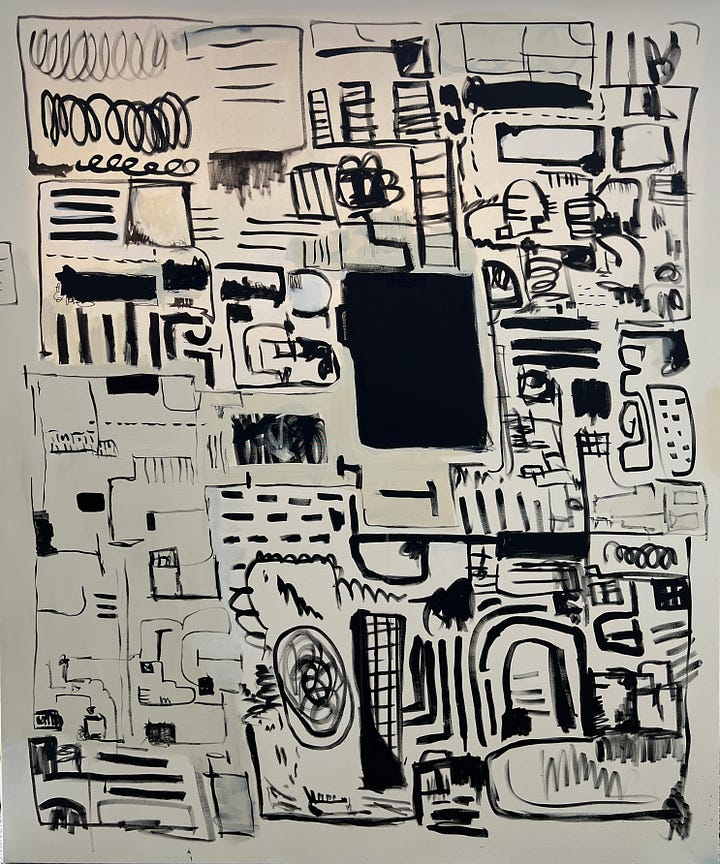

I decided to name all my solo show paintings after immigration forms. These forms encapsulate the general idea of the show: the perfectly designed structure of grids and layouts in contrast with the imperfect, messy, and spontaneous nature of human movement.

In the case of immigration forms, this imperfect human movement manifests in the form of handwriting. Ink that overflows the small spaces designed for our blue pen to stay in. Always Contained.

While thinking about ideas for this show in my studio, I saw a stack of old copies of immigration forms I spent years filling out. I had been debating whether to throw them away or not. Instead I started doodling on them. An unthinkable idea before finishing my naturalization process in 2021. Before then, If there was a fire in my house, my immigration documents would have been the only material possessions I would have taken with me. And now they are just paper sitting on my desk, removed from that life or death character that they once had.

The lines that I started forming, organic and natural were definitely a starting point for everything else you are seeing today at the exhibition.

Lines, geometry, abstraction, and automatic drawings are obviously nothing new. There is a long tradition in art history. Formally they are present in many artists’s work. Examples that have inspired me from a young age include the Mola art of the Indigenous Guna people of Panama and Colombia, Australian indigenous work, the action painting of abstract expressionist Franz Kline, and the work of so many other artists I have longed admired. Brazilian Mira Schendel who also had a profound interest in language, Joan Miro with his automatic drawings, Cy Twombly with his freely-scribbled, calligraphic and graffiti-like works, Rashid Johnson who tells his own stories through abstraction, and obviously my daughters: the queens of gestural crayon on walls, sidewalks and everything in between.

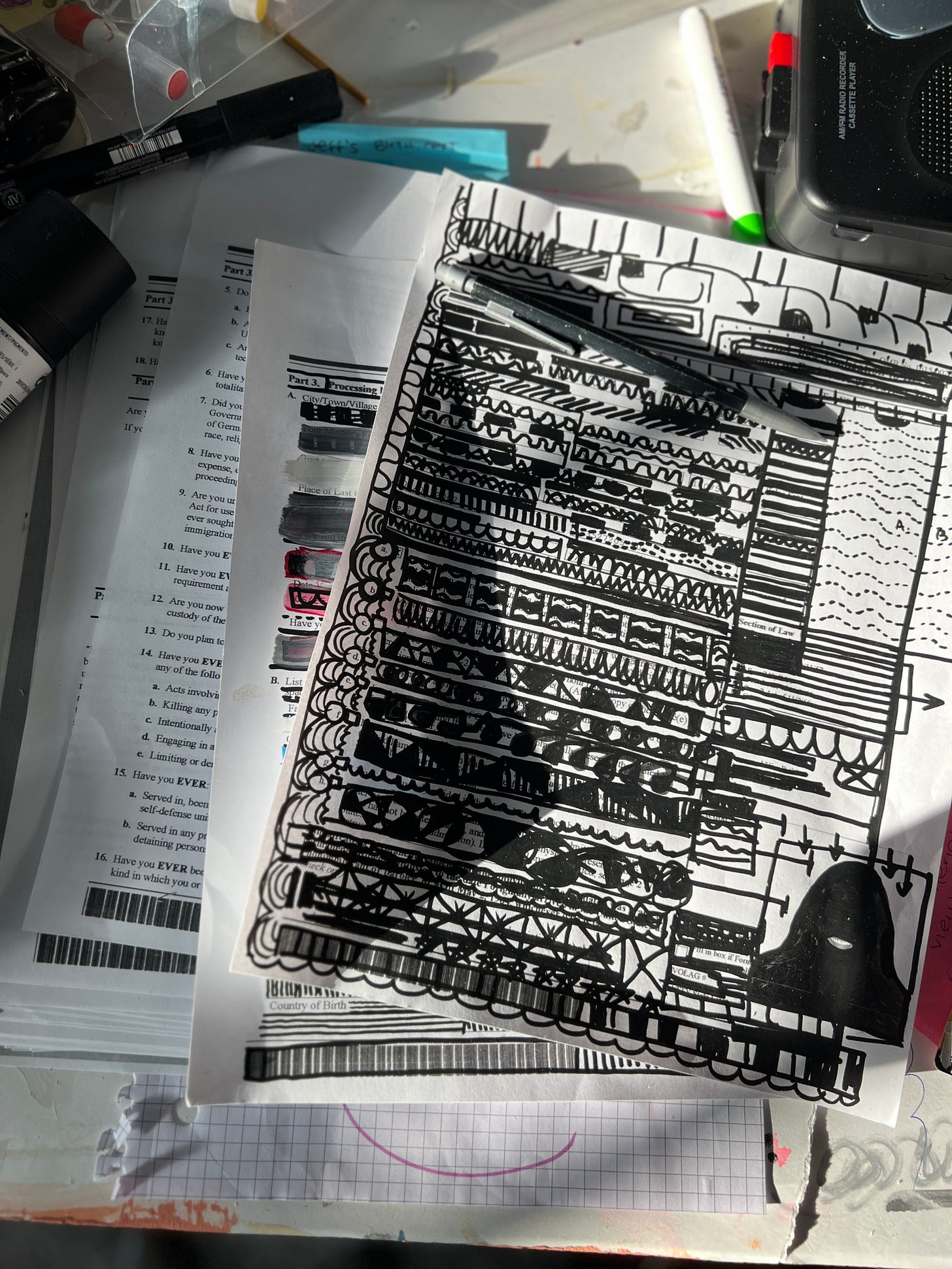

The lines I started forming on the immigration forms also reminded me of this work I made in 2020:

For this drawing, I used the app MapMyWalk to trace my father’s lawnmower paths when he cuts grass at other people’s homes, a job that doesn’t require much interaction and that he chose to do when he emigrated to the United States at an age in which he felt incapable of learning English. I set MapMyWalk on the “wheelchair setting” so my dad’s mower movement could be detected by the app.Through the act of recording his movement I attempted to validate my father’s labor as a form of language.

In this drawing I was also noticing the stability of solid constructions in contrast with the spontaneity of my dad’s lawn mower path.

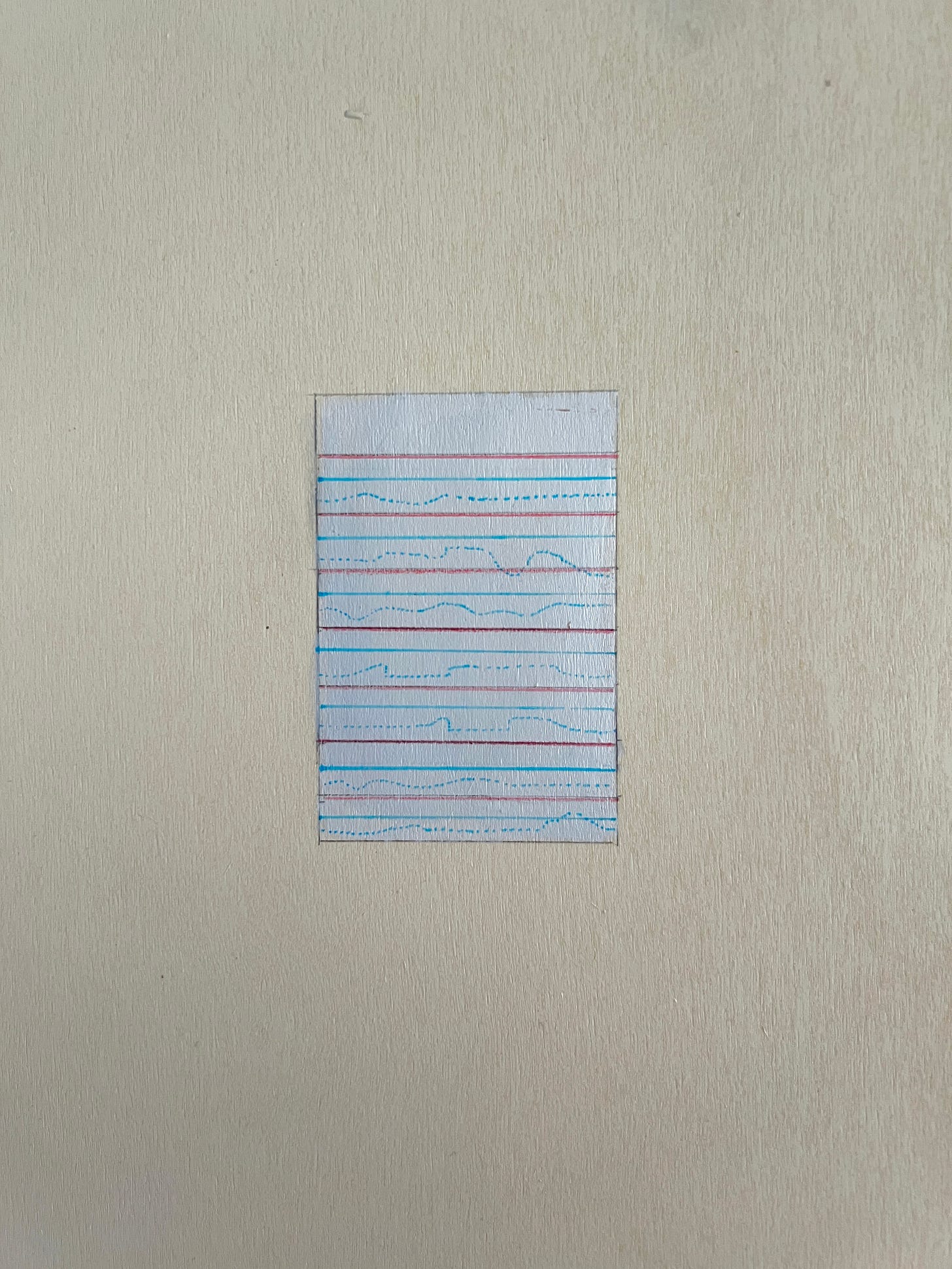

The lines were also present in this piece from early spring:

This drawing is informed by my work as a Spanish translator in a public elementary school in Tallahassee where I assisted a newly arrived immigrant boy named named Lincoln (name changed for privacy) who had no knowledge of the English language to communicate with his teachers and understand his lessons. To create this piece, I re-draw a children's notebook with lines that are generated by spectrogram interpretations of the sounds that immigrants hear during a typical school day. These lines form a visual representation of the language barriers that these children face, which end up resembling the US-Mexico border that many of them once crossed. The piece highlights how this border continues to manifest in different forms, including language barriers.

I visited the United States for the first time when I was 14 years old. I had never been to a foreign country. I had never flown. My first impression from the plane window landing in Miami was how organized the urban landscape was. Neighborhoods perfectly demarcated by manicured lawns, streets parallel and perpendicular to each other forming oceans of concrete grids, pools every two houses that registered like little blue squares from above, the water movement flattened by the distance. This precision mesmerized me.

This fresh paradigm of spatial arrangement stood in stark contrast to the view I had just seen two hours earlier departing from Barranquilla, an aerial landscape that danced to its own rhythm, careless and spontaneous, as if no one was watching. I wondered if Americans down below could see the patterns built especially for them to circulate, to move, to flow.

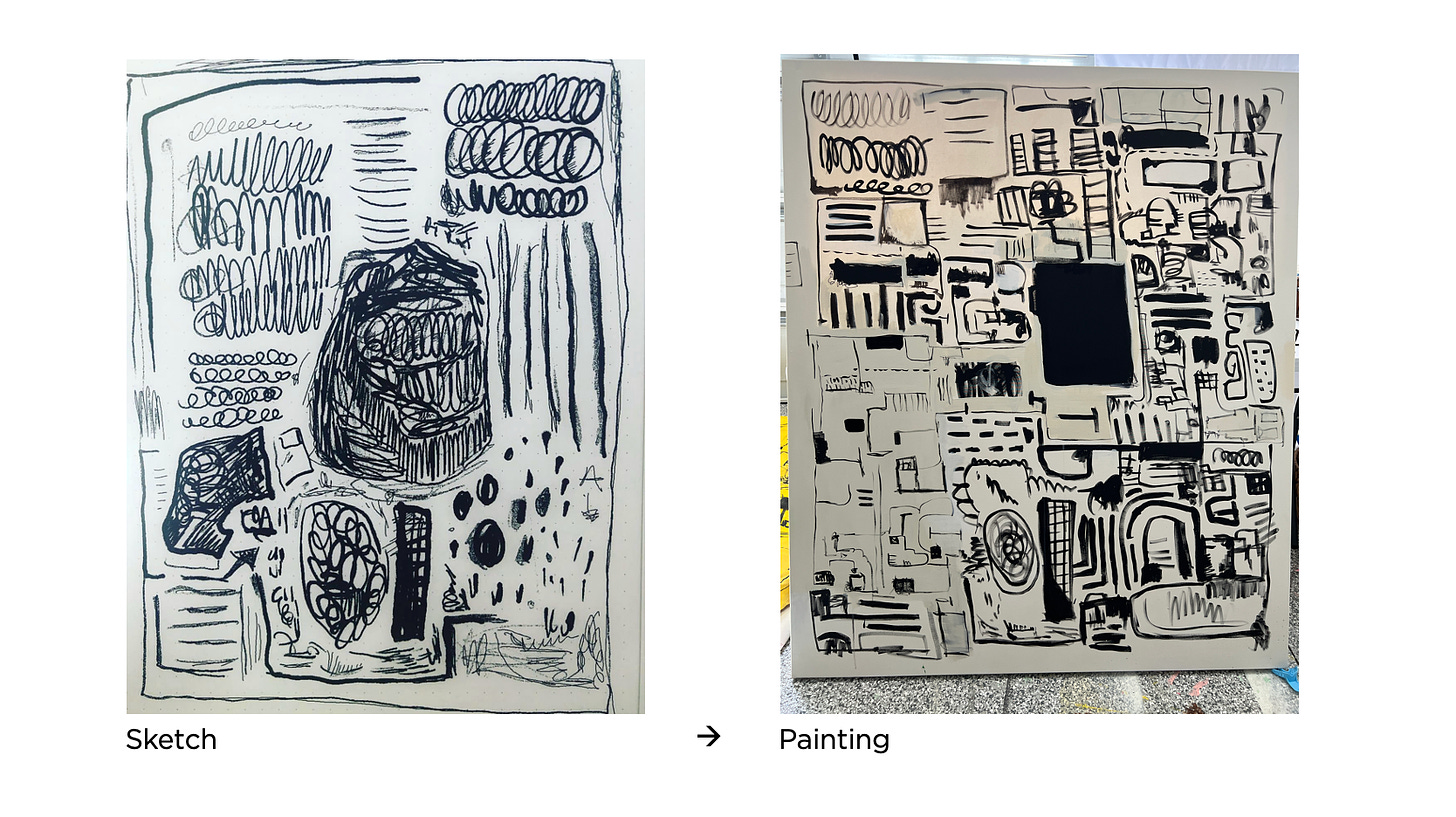

When I wrote the artist statement for the art show that you all probably read, I only had sketches of what I thought the final work was going to look like. I thought the work was only about this geometric patterns I saw from the airplane, about the rigidity versus the spontaneous nature of human movement, about maps and all the things I mentioned on the statement. But As i worked on the actual paintings, I realized that new meanings for the work started to come to the surface.

For instance, how in the act of transferring a sketch to a painting, there was an inevitable loss as the painting never looked like the original. This simple realization made me think of the act of translation.

How drawing is translating, which is something I do in my head every day, I am doing it right now, thinking in Spanish hoping my message will come across fairly similar in English.

An aspiration of accuracy, the precise rules of English grammar being overridden by the clumsy flow of my ideas asking for a way out. Again, the rigid versus the spontaneous.

Crossing borders, linguistic or any type of borders, is a profoundly human process. Extremely vulnerable, so for my paintings I decided to let go of this aspiration of accuracy. I let the hand override the rigidity.

The perfect line, the flawless delineation, the impeccable configuration—they all surrendered to imperfection.

There was joy in that process. It didn’t feel like filling an immigration form. It felt liberating. It felt like dancing. It felt unselfconscious.

I also came to terms with the fact that all the ideas might not be evident in the work. That by you looking at the work you wont probably read all this meaning I am expliaing with words. A

nd that is ok.

Painting as a form of Language is open to interpretation, translation, loss of meaning as well as birth of new one. I gave up on the pursue to To make clever work. I stopped intellectualizing my process. Trying to prove a point. And I just went with it. I let my brush run freely. Form a path like my father’s mower.

It all felt like crossing an imaginary border.

__

The show will be open until February 2024 at the Thomasville Center for the Arts, Thomasville, GA.

Wow! I really loved this, thank you for sharing it