I started writing this newsletter just hours after learning that a mass incidentally found on my spine during a routine MRI was determined to be benign. The incredibly relieving news came after days of incessant and agonizing worry that the mass might not be just a bunch of fat cells but something more serious that could have potentially cut my life short—right when I have school supplies to buy, a meet-the-teacher event to attend, and a first day of 2nd and 3rd grade to document. After hearing the good news, my husband and I cried together, mainly because when faced with the possibility of death, we couldn’t come up with a last wish other than simply returning to the life we have—a life we love in all its quotidian splendor: morning marathons of getting our kids ready for school, dentist appointments, cheer practice, Sundays spent feeling guilty for too much scrolling, and, lately, for me, writing this newsletter, which has given me immeasurable joy.

Last Thursday, on the night I came back from the beach where I wore those cute outfits I showed you in my previous newsletter, my husband kept strangely tossing and turning in bed. I knew he was having trouble sleeping, but I did not attribute it to the second inconclusive MRI result I had gotten a few days ago, as he had been reassuring me from the get-go that, from his medical perspective, the mass the MRI incidentally found on my spine was not something to worry about.

But that night, after being away at the beach for 3 days while he worked back home, Jeff, the most equanimous and stoical man I know, held me tighter than usual. It was 3 in the morning when I woke up to wipe away his tears. I couldn’t tell how long he had been sobbing—I only knew that the last two times I saw him cry was during our two kids’ births. From that night on, we took turns wiping each other’s tears, skeptically reassuring one another that everything was, in fact, going to be okay.

The last tears we shed were of infinite relief, right after we left the neurosurgeon’s office with the benign diagnosis. Those tears, combined with the orange color corrector I put on this morning to cancel out the purple of the dark circles that had been building up for days, soaked Jeff’s Italian wool navy jacket—the one that replaced another wool jacket I ruined with a steamer the one time I tried to play housewife. None of that mattered now. Neither the jacket nor the tears we shed on our anniversary weekend getaway over dinner and dark-humored jokes about death, which we made to pretend we weren’t taking this seriously, to laugh in lieu of crying.

After the great news, nothing else mattered. It was him and I. And my mom on the phone, sobbing in unison because I was going to be fine.

One thing that remained consistent throughout this difficult experience was my conviction in the power of getting dressed.

On the day of our anniversary, with the uncertainty of the diagnosis still weighing on us, I took off a black dress I was going to wear for lunch and deliberately swapped it for a vibrant-colored ensemble.

The colors brought me joy and helped offset disturbing thoughts, like the idea that Jeff and I ordering ribs with ginger and brown sugar, and pizza with fig and duck, must be a sign of a first-sweet-then-bitter future. Or that finding the small designer from the exact same bespoke bracelet Jeff gave me months ago during a trip to Charleston, while we wandered through cute little shops to distract ourselves from thinking about death in 30-second intervals, could only mean one thing: closure.

How distant from God must I be when my thoughts are consumed by such superstitious nonsense?

For our anniversary dinner, I wore an old COS oversized scuba top as a mini dress with black Balenciaga heels. I put on my wedding day earrings. Jeff put on his wedding day cologne. We had fun, but another intrusive thought kept popping up: what if the fact that I didn’t make it into that family photo at the beach in the 10 seconds the timer took to snap the picture without me was a premonitory signal?

The day before the much-anticipated appointment where we received the good news, I wore new Matteau fishermen pants, I accessorized, I put on some makeup for the two-hour road trip to the hospital.

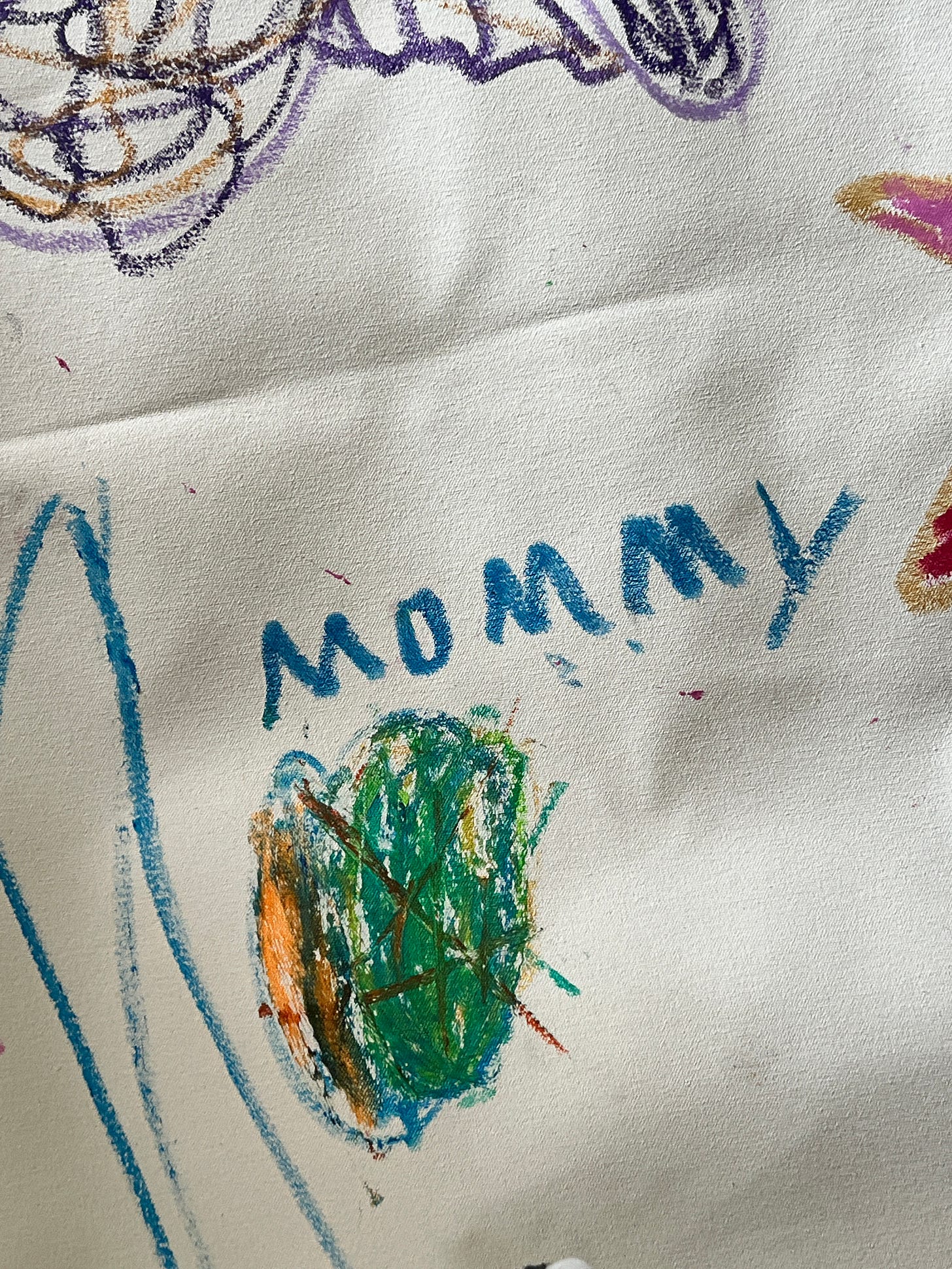

The two-hour road trip in which I cried in silence thinking that that cute little drawing my daughter made me that morning could only be interpreted as an abstraction of my spine mass.

The next day, for the appointment, I adorned myself with my great-grandaunt’s fabulous coral necklace, her ojo de buey pendant with her zodiac sign (Cancer), and one of her many Virgin Marys gold medallitas, all over a peach-colored cotton cardigan she always wore, for there was no time of the year—winter or summer—in which she wasn’t cold. My great-grandaunt, Analuz Morales Manotas—a fabulous woman who moved alone to Manhattan from Turbaco (Bolivar) in her 20s to work at Mount Sinai Hospital as a bacteriologist in the 1950s and never looked at another man after her fiancé died; the one who shared a birthday with my firstborn; the one who received a cancer diagnosis in her 40s and lived until her 90s, who died at my house, surrounded by us, her only family—was deeply present in my thoughts that morning.

Today, probably more than ever, I am convinced that clothes have less to do with empty displays of status, wealth, or taste and way more to do with an experience of spirituality. Clothes not as armor, not to conceal our vulnerability but something Leandra Medine Cohen beautifully described the other day as “heart expanders,” as a moving mediation.

I couldn’t help it. In the midst of it all, I was also looking at fall clothes and planning what to wear for school drop-offs. For birthday parties. For Thanksgiving. Sometimes thinking, “This is what I’m wearing when this nightmare is over.” Other times wondering, “Will the nightmare ever be over?”

The nightmare was over. For now. At least the imminence of it. I came back home from the hospital, hugged my kids who were busy doing their dolls’ hair with my Kerastase leave-in cream, took a long shower, and changed into fresh clothes to gather all their supplies for meet-the-teacher the next day, to exchange the Matteau pants which I ended not wearing as they felt one size too big, to figure out what to order for dinner, to hug my mom, to write, to continue living life—in all its quotidian splendor.

Primero muerta que sencilla (Better dead than basic)—a Colombian maxim.

Joan Didion opens Blue Nights by reminiscing about her deceased daughter’s sartorial choices on her wedding day—the stephanotis she wove into the thick braid that hung down her back, “which inevitably fell after she dropped a tulle veil over her head.”

Karla Cornejo Villavicencio opens her book The Undocumented Americans by describing how long it took her to decide what to wear on the night of the 2016 presidential election, likening her struggle to that of the women on the Titanic who reportedly drowned in their finest clothing, furs, and jewels as the ship sank.

On a breezy summer day, Ana casually wears the same shirt she wore four years ago to cross the border with her two kids. A cute royal blue short-sleeve chiffon top adorned with beaded embroidery details on the back, now tangled from repeated cycles in the washing machine and from the centrifugal memories of her unending hours detained in “la hielera,” where she regretted not wearing something warmer while chasing her American dream.

What do you wear to face adversity? And how does it happen that adversity ends up wearing you, embodying you, and shaping you?

Thank you for sharing the perspective your medical scare bestowed. What we wear tends to be dismissed as trivial, but here you paint a picture of just how meaningful it can be. So happy to hear things turned out alright. Sending ✨️

Thinking of you! So happy you’re okay ❤️